The Most Dazzling Displays at the V&A's Cartier Exhibition

From regal jewels to small acts of résistance, these are the most intriguing pieces to spot at the overwhelmingly shiny exhibition du jour.

The V&A’s summer exhibition, Cartier, opens this weekend in London, and at a preview this week, I was dazzled by the 350 unique pieces on display.

While Cartier the firm was founded in 1847 (after Louis-François Cartier took over a business from his mentor, Adolphe Picard), the exhibition is set around the work of his grandsons, Pierre, Louis and Jacques, who used their complementary skill sets (and strongholds in Paris, New York and London) to build a brilliant global brand in the Art Deco era.

Their work was inspired by their great travels and the leading art and architecture of the day, creating original pieces that are still coveted today, from the iconic Love bracelets to their intricate high jewellery designs.

As well as royal commissions, there are cultural gems to be found throughout the exhibition, from Elizabeth Taylor’s ruby set gifted to her in a swimming pool and Grace Kelly’s engagement ring loaned from the Palace of Monaco to Tyler, The Creator’s Quadrant watch and the Toussaint necklace stolen in Ocean’s 8.

But the real stars of the show are the pieces that tell an even bigger story than their, at times, 235 carats. Shine on!

The Stomacher

The first room of the exhibition looks at the worldly influence of Cartier – from intricate vanity cases in Japanese landscapes, to scarab beetle brooches inspired by the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb in Egypt (which was then displayed at Versailles). In the early 20th century, the French jewellery house often worked with American ‘dollar princesses’ marrying into the English artisocracy. They often opted for the prettiest designs, the French Garlands. Inspired by 18th-century aesthetics but set in innovative and interwoven Platinum settings, they show Cariter’s light touch. The Lily stomacher (Cartier Paris, 1906) also shows their client’s penchant for finding any excuse to wear their jewels – be that on the waist (like this) or even over the shoulder (like Marjorie Merriweather Post). Such styles were designed at the end of another great era in France, the Belle Époque.

In the accompanying book for this exhibition, I found the below note pertinent for our current economic climate, too: “Encapsulating the cult of femininity that ruled the age, these jewels, with their echoes of pre-Revolutionary France, remain potent, poignant symbols of a disappearing world order, the swansong of a leisured, privileged elite.”

Princess Margaret’s Rose Brooch

While the curators of this exhibition seem most excited by Queen Elizabeth’s Williamson Brooch (with its 23.6 carat pink diamond shown alongside concept drawings from Cartier designer Frederick Mew), the best brooch in the collection, in my opinion, is Princess Margaret’s Rose Brooch (Cartier London, 1938). A series of baguettes and brilliant cut diamonds, it appears to unfurl as the observer moves around it. With the middle name ‘Rose’, Margaret wore this sentimental piece to mark her 25th birthday in a portrait by fashion and war photographer Cecil Beaton, and to her sister’s coronation.

Maharaja of Patiala Necklace

Jacques Cartier, in particular, travelled to India many times and formed strong creative partnerships with the maharajahs, bringing an Art Deco sensibility to their treasuries of gemstones. The most significant Cartier commission ever was in 1928 from the Maharaja of Patiala. It includes the Patiala necklace with five rows of 2930 diamonds and two rubies, centred on a 234.65 carat yellow diamond. As modelled by Sir Yadavindra Singh in the 1940s, it was worn with a special choker and covered the whole upper body. The necklace went ‘missing’ during the Indian Independence in 1947 and was ‘rediscovered’ in 1998 in London without its largest gems. The Cartier Collection acquired it and replaced the missing stones with replicas. Even without its real, large gems, it’s hard to fathom the value (and weight) of this necklace in person.

The Wallace Collection

Wallace Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor, has her own expansive cabinet at the exhibition. One of the only pearl necklaces on display, this Flinstonian style was made with pearls gifted by Queen Mary and was arranged in 1956. In 1987, it was sold for charity and picked up by Calvin Klein for his wife, Kelly (who added six pearls to extend it). Although it is likely worth less, I equally enjoyed the avant-garde Tiger lorgnette glasses, which were commissioned in 1954. The Windsors worked closely with Jeanne Toussaint, Cartier's creative director (from 1933 to 1970), as they built “one of the greatest jewellery collections of the 20th century”. Toussaint created jewels for the ‘modern’ woman, with a love of sculpture and textural contrasts. Along with designer Pierre Lemarchand, they would spend hours studying and sketching animals at the zoo, and they created a menagerie of three-dimensional animal motifs, with the panther presiding over the most coveted big cats, including Walace’s infamous Panther Clip brooch, also on display. But here, with their bright yellow diamonds and articulated heads, legs and tales, the Tiger bracelet and clip brooch are “some of the most technically innovative and beautifully made jewels in the Cartier feline menagerie.”

Panther-Pattern Wristwatch

Even before Toussaint, Cartier was known for its striking compositions, including the inspiring panther motif. The Panther-Pattern wristwatch (Cartier Paris, 1914) shows the early marking of irregular polished oynx ‘spots’ and pavé-set diamonds “expertly and minutely cut”. This is the first piece in a series of Panther designs, which leap across one whole wall of the exhibition space. The fascination with big cats is tied to art, design and interiors of the early twentieth century. These animals were so ‘in fashion’, the Marchesa Casati and Josephine Baker even paraded pet cheetahs.

Tutti Frutti

First developed by Cartier Paris, in the 1920s, the Tutti Frutti style was a luscious collection of small pierres de couleur: rubies, sapphires and emeralds that mimicked the shapes of leaves and fruit in a Mughal-inspired style. A joy to behold, these styles make a beautiful bunch. On the left is the Hindou necklace “the most spectacular ever created” (Cartier Paris, 1936, remodelled in 1963), which was first made for Daisy Fellowes, a style setter, Harper’s Bazaar Paris correspondent and heiress to the Singer sewing machine fortune. In the middle is the Mountbatten bandeau, one of the first of the Tutti Frutti (Cartier London, 1928) made in collaboration with England Art Works and bought by Lady Edwina Mountbatten, an heiress, socialite and later the last Vicereine of India. It could also be worn as two bracelets. On the right is a much newer design completed by Cartier in 2024, showing the striking legacy of this design.

The Snake

The jewel that stopped me in my tracks was the Snake necklace (Cartier Paris, 1968) commissioned by the famed Mexican actress and singer María Félix. Between 1966 and 1976, she assembled an extraordinary range of animal-inspired Cartier jewels, conveying the force of her personality. “I like big jewellery, I like volumous pieces, and I quickly realise that Cartier knew how to make them like no one else, and most importantly knew how to make them elegant,” she said. The Snake encapsulates “Cartier's ability to combine aesthetic invention and technical prowess”. Its lifelike movement comes through a highly complex hinged internal structure of platinum, which was adorned with 2,473 diamonds and an underside of scales in black, red and green enamel (the colours of the Mexican flag). It is, simply, astonishing.

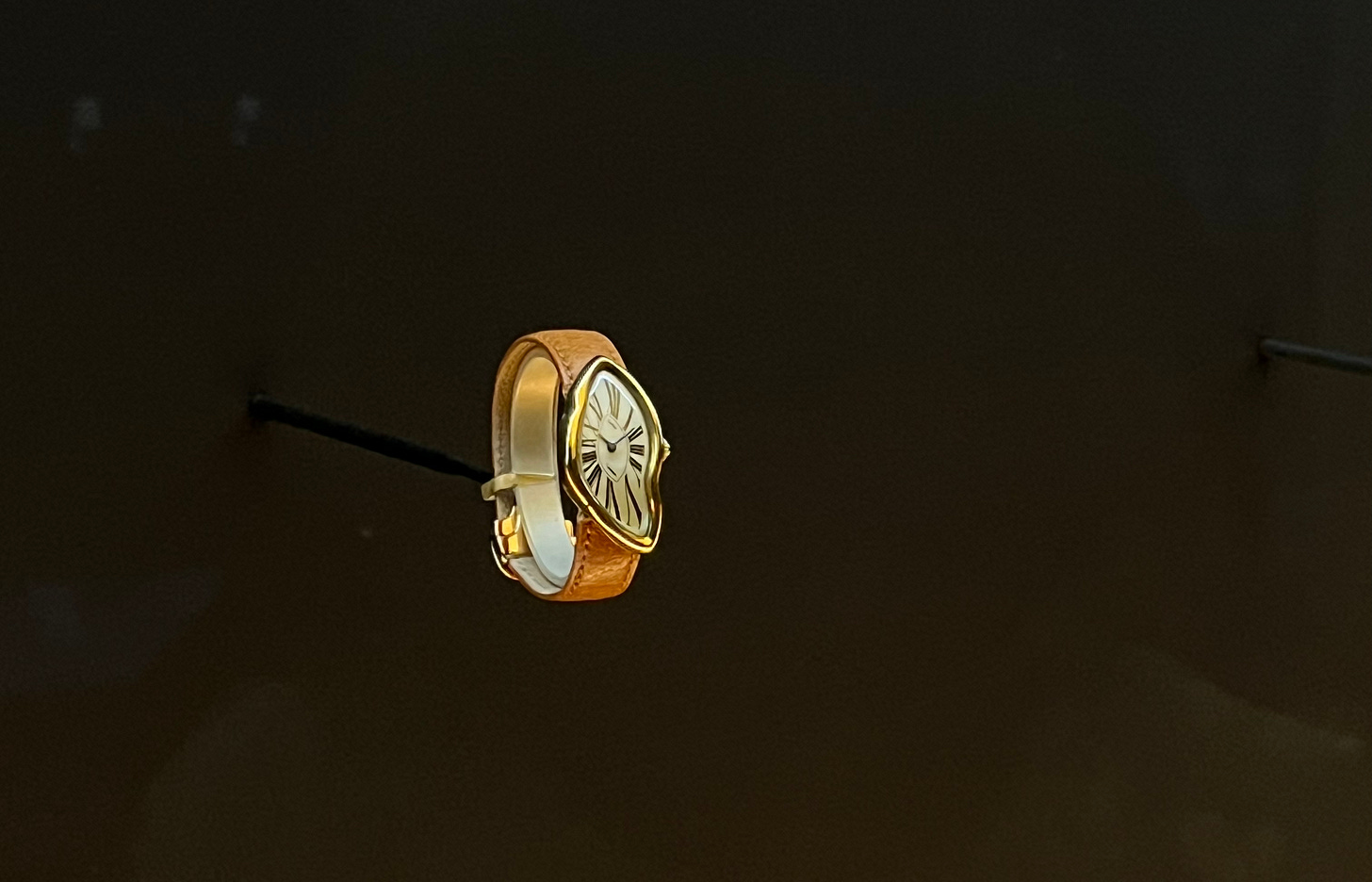

The Crash

Cartier changed the face of wristwatches when the team designed the Santos (Cartier Paris, 1915) for Brazilian aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont, who wanted something that could be easily checked while flying his rudimentary aircraft. Its elegant form – with square as opposed to round dials – inspired many of the Cartier watches made after. This includes the iconic Tank (Cartier Paris, 1920), which was inspired by another vehicle, the First World War tank on the Somme battlefield. Its purity of design meant it was an instant success. But my favourite in the watch cases is the Crash (Cartier London, 1967), designed under the leadership of Jean-Jacques Cartier (son of Jacques) and made by the Wright and Davies workshop. It is subversive and surrealist. In 2022, one sold at auction for a cool US$1.5 million.

The Bird in a Cage

Tucked away in an unassuming corner of the exhibition space is this very loaded cabinet of Wartime brooches. The V&A hasn’t supplied many details about these 1940s designs, but their oral history is told in the Jeanne Toussaint podcast episode of ‘If Jewels Could Talk with Carol Woolton’ which hosts Pierre Rainero, the style, image and heritage director of Cartier today. (Unravelling the legend of Jeanne, it’s well worth a listen.) Towards the end of the episode, they discuss what it would have been like for the creative director and her team to work at Cartier Paris during the German occupation in World War Two. The company took all of their jewellery (including that of Jewish clients) to a hidden location for safeguarding and moved their staff to the southwest. Fearing the failure of the business, Jeanne returned to reopen the Paris store with a small team. To be displayed in the windows, Jeanne designed a small brooch depicting a bird in a cage, in the colours of the French flag – with the obvious symbolism also on show. Jeanne was arrested and imprisoned for three days. (Some say that she was let off with the help of Coco Chanel, who had links to German authorities.) At the end of the war, a new brooch, with the bird out of its cage, flew by the window – liberated at last. In 1955, Jeanne was awarded the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour for her services to jewellery, design and her country.

The Opal Tiara

The most impressive and final room in the exhibition is dedicated to 18 tiaras in all majestic shapes and forms. Cartier London opened its first boutique (on New Burlington Street) in 1902, coinciding with the coronation of King Edward VII, who bestowed the brand a royal warrant and called it “the jeweller of kings and the king of jewellers”. Tiara orders rushed in, and the brand has become known for its ‘unpretentious’ tiaras (if such an oxymoron can exist). Between the Bonaparte olive leaf tiara (Cartier Paris, 1907), the Russian kokoshnik tiaras and a showstopping aquamarine tiara (Cartier London, 1937), you could easily miss the Opal tiara – commissioned by Mary Alice Cavendish (Cartier London, 1937) and displayed for the very first time in public. The striking black opals are likely Australian and were gifted by her husband, the Marquess of Harington, while they were on a government tour of Australia and New Zealand. The tiara was also worn at Queen Elizabeth’s coronation when Mary, then the Dowager Duchess of Devonshire, played the important role of Mistress of the Robes. When pushed at a preview event, one of this exhibition’s chief curators admitted it was her favourite piece from this whole assortment.

Much like this lounging panther (Cartier Paris, 1989), I feel my work here is done. I’d love to hear what your favourite pieces are from this exhibition and whether you’ll be able to see them in all their glory as ‘Cartier’ opens at the V&A.